Origins at Home

The Saskatchewan Conservation House

In 1977, in the windswept prairies of Saskatchewan, a modest building was raised that quietly rewrote the rules of construction. It was not grand. It was not luxurious. Yet it was the most airtight building in the world. The Saskatchewan Conservation House did something radical—it kept the outside, out. It built a future that the world is only now beginning to understand.

Situation: Canada’s Harsh Climate as a Catalyst

The Canadian prairie is a proving ground. Winters that fall to −40 °C. Summers that climb to +40 °C. Winds that scour the land, stripping heat from anything not protected. Before the Conservation House, most Canadian homes were built to survive, not perform. They leaked heat, burned fuel, and demanded constant mechanical effort to make them habitable.

Energy costs in the 1970s were spiking, and questions were rising: could buildings themselves hold the key to security? Could design—not just fuel—keep people safe?

That was the context in which Saskatchewan’s Department of Energy and Mines, along with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, commissioned a bold experiment. The idea was simple but unprecedented: build a house so efficient it could maintain comfort with almost no heating system at all.

Problem: No Standards for True Resilience

At the time, there were no benchmarks for what we now call “high-performance” building. Building codes were blunt instruments—focused on minimum structural safety, not energy performance.

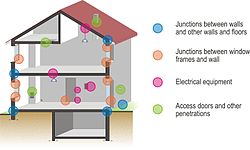

The reality was stark. Prairie homes bled heat through uninsulated walls, drafty windows, and unsealed junctions. Furnaces ran endlessly, guzzling oil and gas. Residents were hostages to fuel supply, not masters of their environment. The problem wasn’t just inefficiency—it was fragility. If the furnace failed in a Saskatchewan winter, the house itself failed.

This is the absence of resilience. And in 1977, no standard existed to address it.

Solution: Super-Insulation, Airtightness, Ventilation—Without a Furnace

The Conservation House project team broke from convention. They rethought the building envelope as a system. Their innovations included:

- Super-Insulation: Walls insulated to unprecedented thickness, reducing heat loss to a fraction of typical homes.

- Airtight Construction: The house was sealed meticulously, with airtightness measured and confirmed—a practice that was unheard of in conventional construction.

- High-Performance Windows: Triple-glazed, well-sealed windows kept heat inside and drafts out.

- Heat-Recovery Ventilation (HRV): A ventilation system that exchanged stale indoor air for fresh outdoor air—while capturing and reusing the heat. This was one of the world’s first practical applications of HRV.

- No Furnace: Instead of a conventional heating system, the house relied on passive gains—sunlight, body heat, appliances—augmented by a tiny electric coil in the ventilation system.

The result was transformative. The house consumed roughly 90% less energy for heating than a typical prairie home of its era. It did this not by burning fuel more efficiently, but by needing almost none at all.

Consequence: A Global Precedent, Still Standing

The Saskatchewan Conservation House did more than work—it thrived. It demonstrated that it was possible to build in Canada’s most punishing climates without reliance on oversized mechanical systems.

Its influence spread far beyond Saskatchewan. German researchers visiting the project carried lessons back to Europe. These principles became the foundation of what is now known as the Passive House standard—codified in Germany in the 1990s and recognized today as the world’s most rigorous voluntary building performance standard Passive House Canada, Wikipedia.

And the Conservation House itself? Nearly fifty years later, it's still in use, still performing, still standing as proof that Canada was there at the beginning.

Why It Matters: Canada’s Legacy Is Your Foundation

When Canadians hear the term “Passive House,” they often think it’s a European import. The truth is the opposite. The DNA of Passive House was born here, on the prairies, under our sky. The Saskatchewan Conservation House is not a relic—it's a blueprint.

If Canada could pioneer airtight super-insulated construction in 1977, with none of today’s materials, modelling tools, or prefabrication methods—what excuse remains in 2025?

This matters because Passive House is not an ideology. It's survival and sovereignty encoded in construction. It's comfort, health, and independence—built into walls, roofs, and windows. Canada’s first experiment proved the concept. Today’s builders, policymakers, and homeowners must decide whether they will carry it forward.

The lever is clear: Canada does not need to import resilience. We already wrote the book. The only question is whether we will read our own history—and act.

This is what I’m working on. Tell me what you think, I enjoy the conversation! Subscribe and follow the work in real time.

Thanks!

B

The world’s first Passive House was Canadian.

1977. Saskatchewan.

While others burned fuel, we built walls that held heat like stone.

No furnace. No fallback. Just design that defied −40°.

Our legacy is the foundation. Why aren’t we standing on it?

PS -